Mark Kostabi on Dancing on the Roof: Phtography and the Bauhaus

One of my favorite TV shows has always been Batman, starring Burt Ward. Not only because of Cat Woman, the Bat Cave and the Joker, but because of those great shots where the camera was joyously tilted at a dynamic angle. Many amateur photographers have taken pictures with the same idea, but usually end up with gimmicky and corny results. Those who could actually pull it off include the creators of Batman, and their predecessors: a number of Bauhaus photographers like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Lux Feininger. Dancing on the Roof: Photography and the Bauhaus (1923-1929) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, explores this period of freewheeling innovation – which began when master instructor Laszlo Moholy-Nagy arrived at the progressive German art school, and ended when photography became an official part of the school’s curriculum. The exhibition presents about 60 photographs by a dozen artists.

Founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus was a utopian haven for avant-garde artists during the period of dramatic change and tenuous peace between the two world wars. United in their goal to create new art for a modern industrialized age, the Bauhaus artists, who included Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger, Albers, Breuer, and Schlemmer, among others, embraced novel techniques and free experimentation. Yet while architecture, graphic and furniture design, metalwork, weaving, and theater all had official workshops at the Bauhaus before 1929, photography did not.

Liberated from the expectations of a formal course, photography was practiced in a playful, exploratory manner which enchanted Bauhaus masters and students alike. Boldly fusing ideas absorbed from Dada, Surrealism, Russian Constructivism, illustrated newspapers, avant-garde film, and jazz, these artists created images that reflect both the dynamism and turbulence of the era, and the optimism, energy, and experimental liberties of life and work at the Bauhaus. Although Moholy-Nagy never formally taught photography during his years at the Bauhaus (1923-1928), he exerted enormous influence through his groundbreaking photographs and writings, in which he advocated unusual vantage points, extreme close-ups, radical cropping, negative printing, and cameraless photography.

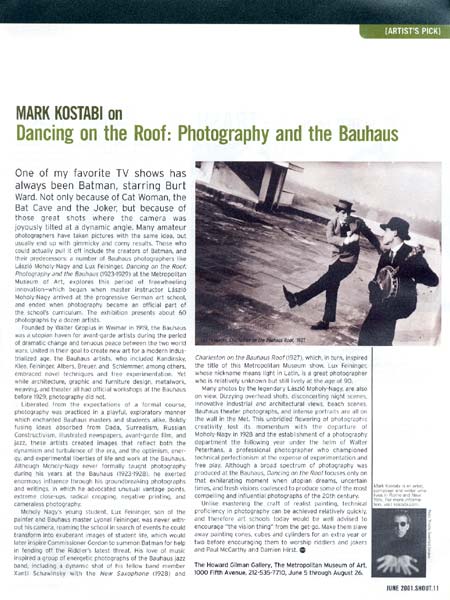

Moholy Nagy’s young student, Luz Feininger, son of the painter and Bauhaus master Lyonel Feininger, was never without his camera, roaming the school in search of events he could transform into exuberant images of student life, which could later inspire Commissioner Gordon to summon Batman for help in fending off the Riddler’s latest threat. His love of music inspired a group of energetic photographers of the Bauhaus jazz band, including a dynamic shot of his fellow band member Xanti Schawinsky with the New Saxophone (1928) and Charleston on the Bauhaus Roof (1927), which, in turn, inspired the title of this Metropolitan Museum show. Lux Feininger, whose nickname means light in Latin, is a great photographer who is relatively unknown but still alive at the age of 90.

Many photos by the legendary Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, are also on view. Dizzying overhead shots, disconcerting night scenes, innovative industrial and architectural views, beach scenes, Bauhaus theater photographs, and intense portraits are all on the wall at the Met. This unbridled flowering of photographic creativity lost its momentum with the departure of Moholy-Nagy in 1928 and the establishment of a photography department the following year under the helm of Walter Peterhans, a professional photographer who championed technical perfectionism at the expense of experimentation and free play. Although a broad spectrum of photography was produced at the Bauhaus, Dancing on the Roof focuses only on that exhilarating moment when utopian dreams, uncertain times, and fresh visions coalesced to produced some of the most compelling and influential photographs of the 20th century.

Unlike mastering the craft of realist painting, technical proficiency in photography can be achieved relatively quickly, and therefore art schools today would be well advised to encourage “the vision thing” from the get-go. Make them slave away painting cones, cubes and cylinders for an extra year or two before encouraging them to worship riddlers and jokers and Paul McCarthy and Damien Hirst.

June 2001