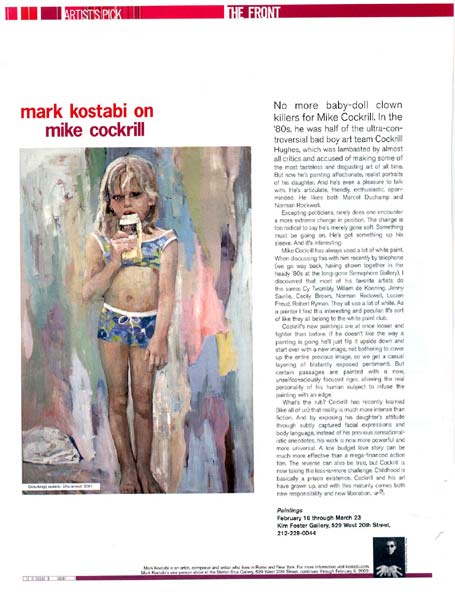

Mark Kostabi on Mike Cockrill

No more baby-doll clown killers for Mike Cockrill. In the ’80s, he was half of the ultra-controversial bad boy art team Cockrill Hughes, which was lambasted by almost all critics and accused of making some of the most tasteless and disgusting art of all time. But now he’s painting affectionate, realist portraits of his daughter. And he’s even a pleasure to talk with. He’s articulate, friendly, enthusiastic, open-minded. He likes both Marcel Duchamp and Norman Rockwell.

Excepting politicians, rarely does one encounter a more extreme change in position. The change is too radical to say he’s merely gone soft. Something must be going on. He’s got something up his sleeve. And it’s interesting.

Mike Cockrill has always used a lot of white paint. When discussing this with him recently by telephone (we go way back, having shown together in the heady ’80s at the long-gone semaphore Gallery), I discovered that most of his favorite artist do the same: Cy Twombly, Willem de Kooning, Jenny Saville, Cecily Brown, Norman Rockwell, Lucien Freud, Robert Ryman. They all use a lot of white. As a painter I find this interesting and peculiar. It’s sort of like they all belong to the white paint club.

Cockrill’s new paintings are at once looser and tighter than before. If he doesn’t like the way a painting is going he’ll just flip it upside down and start over with a new image, not bothering to cover up the entire previous image, so we get a casual layering of blatantly exposed pentimemti. But certain passages are painted with a new unselfconsciously focused rigor, allowing the real personality of his human subject to infuse the painting with an edge.

What’s the rub? Cockrill has recently learned (like all of us) that reality is much more intense than fiction. And by exposing his daughter’s attitude through subtly captured facial expressions and body language, instead of his previous sensationalistic anecdotes, his work is now more powerful and more universal. A low budget love story can be much more effective than a mega-financed action film. The reverse can also be true, but Cockrill is now taking the less-is-more challenge. Childhood is basically a prison existence. Cockrill and his art have grown up, and with this maturity comes both new responsibility and new liberation.

February 2002