Mark Kostabi on Tracey Baran

Tracey Baran’s favorite movies include Frankenstein, because “it was so beautiful,” and American Beauty, because she “was in it” – metaphorically. Baran was initially known for painfully real, intricately detailed photos of a bluntly dysfunctional family. Hers. A few years ago, when I first climbed the stairs of 552 W. 24th Street and entered the small Liebman Magnan Gallery, I was overwhelmed by Baran’s intense vision of her own strained family relationships. A landscape of discarded, decaying consumer packages enveloped her family members as they inertly laid about in their physically and emotionally ravaged home. Ants crawled over crumbs on a plate as an adjacent ant trap held out in vain for occupants. As a confirmation of suffocating American middle-class malaise, Baran also included herself in these environmental portraits as a sign of her acceptance of a life where empty cartons and packages replaced her words.

Baran’s second New York show was quite different, leaving behind the domestic decay. Saturated with flesh, it focused instead on her own developing sexual awareness, and conflicting feelings about sexual purity, shame, and taboo.

Now, Baran again refuses to lock into a signature style. The new work, titled Still, includes portraits and landscapes. Among the nine 30 x 40 inch color photos is a striking image of a heap of discarded pigs, which the artist found near her home in upstate New York. Another remarkable photo documents a pile of used Christmas trees. Both images explicitly comment on our shamelessly wasted society. Baran, unlike her well-known contemporaries, Justine Kurland, Anna Gaskell and Malerie Marder, never stages her imagery. It’s all found, and she only uses available light. She is the opposite of the School of Crewsdon.

The most obvious comparison to Tracey Baran is the young British artist Richard Billingham, who was in the legendary Sensation show. Although both artists photograph their own rough-around-the-edges families, the difference lies in their unique emotional resonance.

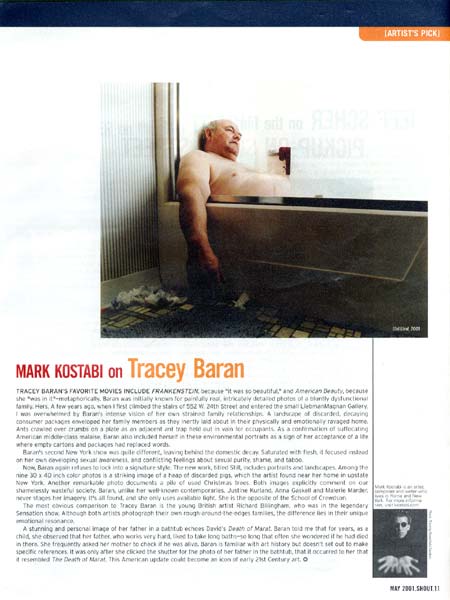

A stunning and personal image of her father in the bathtub echoes David’s Death of Marat. Baran told me that for years, as a child, she observed that her father, who works very hard, liked to take long baths – so long that often she wondered if he had died in there. She frequently asked her mother to check if he was alive. Baran is familiar with art history but doesn’t set out to make specific references. It was only after she clicked the shutter for the photo of her father in the bathtub, that it occurred to her that it resembled The Death of Marat. This American update could become an icon of early 21st Century art.

May 2001